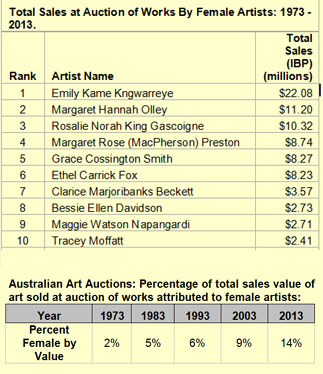

Thanks also to a big contribution from another section of the community that has been the victim of a different social equality bias – Aboriginal art - the value of art by women artists as a percentage of the total value of art sold at auction in Australia has grown from 2 per cent in 1973 to 14 per cent in 2013.

The gap still has a long way to go but, the Cormack sale in Sydney on July 5 and 6 showed that Australian women artists work is being drawn into the saleroom because more women artists have been produced in the contemporary period than any other period and we are now reaching the period where these works are being passed to the next generation, via the resale market.

The decade showing the strongest increase in sales of women's art work was in the last 10 years when the value of art by women artists as a percentage of the total value of art sold at auction in Australia increased 5 percentage points.

The biggest new contributor over the 40 years was the Aboriginal artist Emily Kngwarreye who was not even active when the AASD records commenced.

She contributed $22.076 million to the total value of women's art sold at auction over that period. She also greatly narrowed the gap between the record prices paid for women versus men artists' work.

In 1973 record price was $60,000 for William Dobell's The Dead Landlord. The highest price paid for a woman's work in that year was $1300 for a Carrick Fox.

By the end of 2013, the auction record for a male Australian artist was $5.4 million for Sidney Nolan's First Class Marksman 1946 sold by Menzies Art Brands on 25 March 2007, and for any woman's work, $1,056,000 for Emily Kngwarreye's Earth's Creation, 1995 sold by Lawson-Menzies on 23 May 2007.

Maggie Watson Napangardi was the ninth best selling woman artist on the 50 year list at $2,711,542.

Aboriginal women artists contributed $3.3 million or 24 per cent of the total sales of $13.7 million of women's art at auction in 2013 despite the parlous state of the market in contemporary Aboriginal art.

While Emily's and Maggie's contributions give a more daring subject trend to the women's work, the rise of contributions from other top selling non-indigenous women have helped swing Australian art collecting in the direction of art that is “easy to live” with – flower paintings in particular.

Margaret Olley who is number two at $11.2 million in total sales value from 1973 to 2013, and Grace Cossington Smith at $8.27 million, were flower or comfortable interior painters. By and large Carrick Fox painted flower markets.

Australian collectors might pay more for an Olley than for a work by Fantin-Latour, one of last century's great French flower painters.

But the only overseas artist on the 40 year list is a woman – at number 15 with $2.29 million.

That is the British artist Bridget Riley, her position due entirely to buying by a Sydney decorator, the late Lex Aitken from whose estate they were all sold and returned to British buyers at a Sydney auction.

Overseas appreciation of more challenging women's work occurred this month with the sale at Christie's in London of Tracey Emin's My Bed for £2.5 million.

But fellow British artist Damien Hirst's (Shark Tank) – a similarly challenging installation - made between $US8 million and $US12 million on the dealer market in 2004 according to which account you accept.

Tracey Moffatt puts tougher women's art into the Australian equation with her appearance at 10th place with $2.41 million, but she is closely followed by 11th placed Elizabeth Durack's more easily read subjects at $2.31 million.

It was another woman who took up art, like Emily, in her advanced maturity, and took it in a new direction with her art of lettered packing case planks that gives an edgy touch to the top 10 women.

New Zealand born (1917-1999) Rosalie Gascoigne with toal sales of $10.3 placed her at number 3, despite her not readily accepted medium of knocked together packing case planks.

Attractive as they are, and neglected as she may be, Clarice Beckitt's work is still easy to live with and it is no surprise that she is there at number 7.

Her asking prices lately have been taken to Whistlerian heights on the dealer market, where some of the market has taken shelter in the uncertain financial climate, by Niagara Gallery.

Intrepid artist Mary Ellis Rowan who tramped the New Guinea jungles in her 80s and was a tough price negotiator with the Australian Government for her work, is placed at 16th.

For women to make sculpture may have been more scandalous than painting oils, so Bronwyn Oliver is the only sculptor to make the top 20 list at number 13.

Janet Cumbrae-Stewart is number 18th but would have been much higher if the list were compiled in the 1980s when Dana Rogowski and a different school of dealers were promoting her.

Support for women's art in Australia may have begun from a low base because Australia was always seen as a man's country.

Older Australians will remember the near segregation of men and women in pubs (and certainly the voluntary segregation of men and women at social gatherings) - and abysmally they will note the lingering segregation or isolation of Aborigines in the same situations.

Gender equality may never be complete here because of the limited number of 19th century women artists in Australia.

Women were kept out of mischief by being encouraged to knock off a watercolour in an hour or two when they were not busy with their needlework.

There was a small band who broke the “canvass ceiling” because they were good, believed in themselves and intrepid in pursuit of subjects and patrons.

Adelaide Ironside achieved some international esteem particularly in Rome with her religious paintings but there are not enough of these to offset the much larger output of men's art in the 19th century.

Paradoxically equality may be more approachable in Australia where locally produced art dominates the market because from the Renaissance women were very much in the minority as artists overseas.

Judith Leyster is one of the few who rose to the surface “albeit” with flower paintings.

Artemesia Gentileschi has been the subject of a lot of interest in recent times, but her brutal portrayals of the death of John the Baptist were not comfortably identified with a woman artist by past generations of taste-makers.

The recent growth also reflects the big expansion of women studying art both as practitioners, dealers and researchers.

In the 1970s the then director of the National Gallery of Australia began adding the work of Australia's 1930s printmakers to the gallery's collection.

A batch of works by another elderly lady, the little known 101 year old Helen Baldwin alerted many saleroom buyers to her talent.

Market pressures resulted in the work of many “overlooked” women artists coming to the fore with the "dug up" movement of the 1980s.

Women were edited out of art history, it has been argued, because art history has been written by men.

Australian women's art enjoyed the very focussed attention of Professor Joan Kerr whose Heritage: The National Women's Art Book appeared in 1988 with a painting by Mary Edwards on the cover.

Germaine Greer wrote her book The Boy in 2003 adding to the limited stock of literature on Australian art written from a woman's viewpoint.

Many other books on individual or groups of Australian women artists were published over this period.

The sheer demand for fresh works in the 1980s drew out many forgotten women artists.

The disadvantaged woman artist is brought up nearly every time a gallery has an exhibition of the work of woman artists, who often asked big prices initially.

In 1919 Hilda Rix Nicholas was asking 1000 guineas for the painting Desolation.

In hard times women suffered with men, if not more so, as the role of the male as a breadwinner then came seriously into play.

A writer to the Sydney Morning Herald (November 20, 1930) who signed herself an “unemployed lady artist” said that a lot had been heard of public bodies helping the unemployed in the trade and the professions but nothing about helping the artist.

A friend of hers had advertised for an unemployed lady artist and had over 200 replies. The answer, she suggested, might be an exhibition of works for Christmas presents.