For the museums the lot presents a major conundrum - which institution is to go for it and how is the tragic story it embraces is to be told.

By law they cannot collude as far as price is concerned and might have difficulty doing so on other matters if they proceed to try to make a purchase

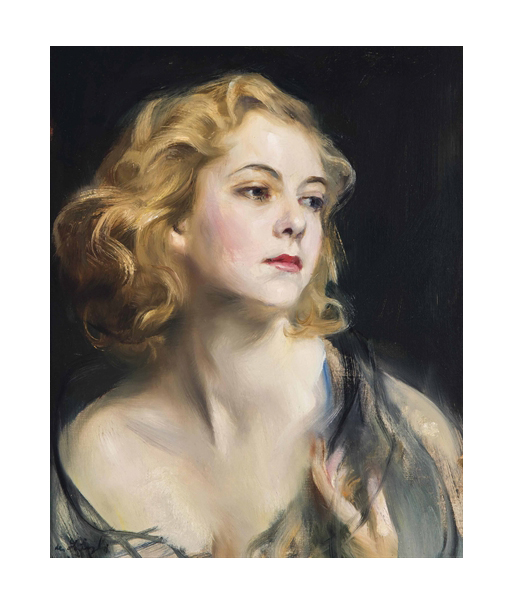

The lot is a very lovely portrait of a beautiful young lady but it is by an artist, Philip de Lazslo, who has only lately emerged from the “Culture Bin” of art history because his facility as a social portrait painter was derided by the art elite.

Its importance as art, however, is overshadowed by its significance as a piece of social and political history. It is one of the most tangible links to an episode which became known as The Little Digger’s Darkest Secret.

The secret was kept for several decades, to emerge only after time and changed social attitudes made it more presentable for the public. Its acquisition is a story worth telling of how attitudes have changed and become more compassionate.

The sitter for the portrait, Miss Helen Hughes, was the wartime leader Billy Hughes’ only daughter by his second marriage, and she died suddenly in London in August 1937 after going to London – according to the press – to attend the 1937 Coronation. Although it was not the coronation expected, due to the abdication of Edward VII, she still had the opportunity to attend the coronation of George VI, that was to be held on the same date that Edward’s coronation was proposed.

The King’s romance was another little secret kept from much of the English speaking world for some time.

The unwed Helen Hughes was still in London for a caesarean section, not an abortion as had been whispered amongst society. Following the operation she developed sepsis which the long suppressed birth certificates cited as the cause of death.

The situation was akin to one outlined in Downton Abbey involving Lady Edith. Lady Edith's child was adopted but she sought to regain him from the adopted family.

Helen’s body was brought back to Australia for a public funeral but the secret remained secure. The unacknowledged son of the unknown father survived and came back to Australia where he reportedly changed his name and has lived in anonymity. Billy Hughes, who was no stranger to births outside wedlock, was devastated. Helen boasted she could twist him around her little finger.

Christie’s catalogue tells nothing of the tragic story, possibly by choice.

She was a charmer who danced with the Duke of Gloucester at a State Ball at Parliament House. She was in demand to model clothes at charity functions; she was noticed. She is reputed to have said “if Daddy is cross with me I just pick him up, for he is very little”.

Until her death certificate was traced in 2004, the cause of Helen Hughes’ death was known only to a few, but followed a 24-hour labour before giving birth to a son by caesarean section.

Curators of a few national institutions must be mulling over the seductive portrait which conceivably could find a place for it, from the Museum of Democracy to the Museum of Australia, but above all the National Portrait Gallery (NPG), despite the artist’s reputation for slickness.

The work has only a brief catalogue entry. It reads:

Philip Alexius de László (1869-1937)

Portrait of Helen Beatrice Myfanwy Hughes, head and shoulders, three-quarter profile to the right, wearing a dark blue chiffon stole around her bare shoulders, her left hand raised, signed and dated 'de László/1931. X' (lower left), numbered '276' (on the reverse) and with inscription in John de Laszlo's hand 'Helen Hughes, aged 17, daughter of / Rt Hon. William Hughes, late Prime / Minister of Australia.' (on the reverse), oil on canvasboard, 20 x 16 in. (50.8 x 40.7 cm.)

The estimate is £15,000 to £25,000.

Upon De Laszlo;s death, coincidentally within a few months of Helen’s, the Australian artist John Longstaff described De Laszlo, a Hungarian artist who lived in Hampstead “a little superficial.” Another Australian artist James Quinn said he was “a little thin.”

However, he painted most of the crowned heads of Europe, many members of the aristocracy and whoever could afford him.

The South Kensington rooms have been possibly more productive for Australian collectors and dealers than Christie’s main rooms in St James’ because of the period they covered. They tended to handle works from the period Australia was developed…although theoretically they should be buying works leading up to foundation, of course, as we did not accumulate any contemporaneously.

The NPG only recently obtained a portrait catalogued as Bligh of the Bounty which had been offered in its room in November 1979. The portrait then sold for a song to an English collector because of a “mutiny” by would be bidders, due to doubts about its authenticity. These dogged it for years.

The lack of absolute conviction that the portrait was Bligh resulted in the painting selling at CSK well under the estimates. The portrait was knocked down to a private collector in England, Mr Stephen Walters, who apparently was buying on someone else's behalf.

Many pieces of Australiana including early Australian silver have turned up at South Kensington although they have not always been bought by or for Australians.

In November 1983 David Attenborough purchased several Aboriginal artefacts there in person. I know because it was a morning sale and I arrived bleary eyed from Heathrow after the 25 hour flight from Sydney, putting matchsticks between my eyelids to keep them open.

Determined to find out who the fellow was in the crowded room buying Aboriginal artefacts was, and then make my way to the hotel, I buttonholed him and asked him. He gave me his card and when I looked at it I looked up in shock and horror. He was, I must add, not quite so well known then.

Many of Christie’s Australian art sales have been held in the same rooms, and together with travel posters and sporting memorabilia sales have contained many important lots of Australian interest, especially cricket.

An early Australian billiard table was sold to an American buyer. The Powerhouse Museum bought an old Baird TV and in 1984 for $30,000 an Enigma decoding machine of the variety which helped the Allies win World War II, $365,183, which was about three times the auction house's estimate. A rare telescope bought at a Parramatta auction for $540 turned up there in 1986 with an estimate of £8000, and sold for a price which did not disappoint.

Tasmanian antique dealer John Hawkins paid £2340 in 1984 for Sir Joseph banks 12 specimen cabinets when they were de-accessioned by the British Museum. They were sold to Warren Anderson for an undisclosed price and then made $250,000 at the property developer’s Owston sale in Sydney in 2010, going to an anonymous buyer, reputed to be Kerry Stokes.

Ros Packer obtained a novelty claret jug there for the form of a kangaroo for £60,000.

A Christie's spokesman told ATG: “We are proposing to stop sales at CSK but this is subject to consultation and not concluded for at least a month.”