The portrait appeared at an auction at Mount Juliet in Ireland on September 24 1986 when it was sold by Sotheby's for £40,000 plus buyer's premium against an estimate of £350-450 despite not being illustrated in the catalogue of the sale.

A few months later the portrait was sold to the National Maritime Museum at Greenwich for £600,000.

The inspired buy was made by David Posnett, of Mayfair's Leger Gallery. It was subsequently identified as the work of Hodges, and not a copy, and which had previously been "whereabouts unknown." The image of Cook was repeated in early engravings.

Posnett is the doyen of the sleeper and arbitrage world. He famously bought a Conrad Martens painting which he discovered in a British middle counties cowshed. But he exercised his Cook credentials in Australia when he cast judgment on a "Zoffany" group portrait of Captain Cook, Sir Joseph Banks and Lord Sandwich bequeathed to the National Library in Canberra.

With Zoffany's name attached, the group portrait would have been of enormous value if correct.

The group portrait was left to the library by a member of Melbourne's Meyer family which acquired it from Christie's in the 1930s as a Cook portrait by the famous artist Johann Zoffany.

Posnett said on said on his evidence, simply by looking at a newspaper clipping illustrating the work, it was by John Hamilton Mortimer (1741-1779) whose work was often mistaken for Zoffany's.

"The composition was not sophisticated enough for Zoffany," Mr Posnett said.

Australia has its own contemporary portrait of Captain Cook which Mayfair dealer Lady Angela Nevill and Christie's Roger McIlroy sold to our own National Portrait Gallery in Canberra for $5.1 million in 2001.

Our own Webber portrait (the Canberra work) shows a very posed Cook in a powdered wig.

It first came up at a Melbourne auction in 1983 when it made $506,000 plus buyer's premium of 10 per cent in one of Sotheby's first sales in Australia when it was bought by Lady Angela Nevill for Alan Bond, about to become the exultant sailor responsible for promoting its win in the Americas Cup.

Although it is not known how the proceeds were divided up, the price must have brought a cheer to the old seamen who had received sustenance from Trinity House in Hull where it had been undisturbed for aeons.

That it had seemingly been forgotten about may help explain how the portrait escaped the intervention of Britain's heritage authorities who are charged with protecting Britain's portable national heritage.

When Ken Hince, the Melbourne bookseller, thought to have been acting for the State Library of NSW, was asked why he underbid the portrait at Sotheby's Australia he made the now legendary remark he was bidding for stock.

Scallywags asked if it was stock for his shop or for Melbourne heart surgeon Dr Eric Stock who was a collector of this period and material.

Such was the generous over-the-estimate price it achieved. Lady Angela secured the portrait for Bond Corporation so she had two goes at it. During the sorting out of Bond's affairs, post the 1987 crash, the portrait had a holiday in Switzerland in unpublished hands. The affair was too early for the Panama Papers to throw any light on it.

Bond was to find out himself during these years how difficult Britain's heritage laws could be.

He was refused permission to take Benjamin West's Portrait of Sir Joseph Banks, out of the UK after buying it there at auction. The authorities are entitled to stop works leaving the country if a local buyer cannot be found to match the price.

Bond refused to sell it and was allowed to keep it in Britain. He did this for several years before offering it back on the market.

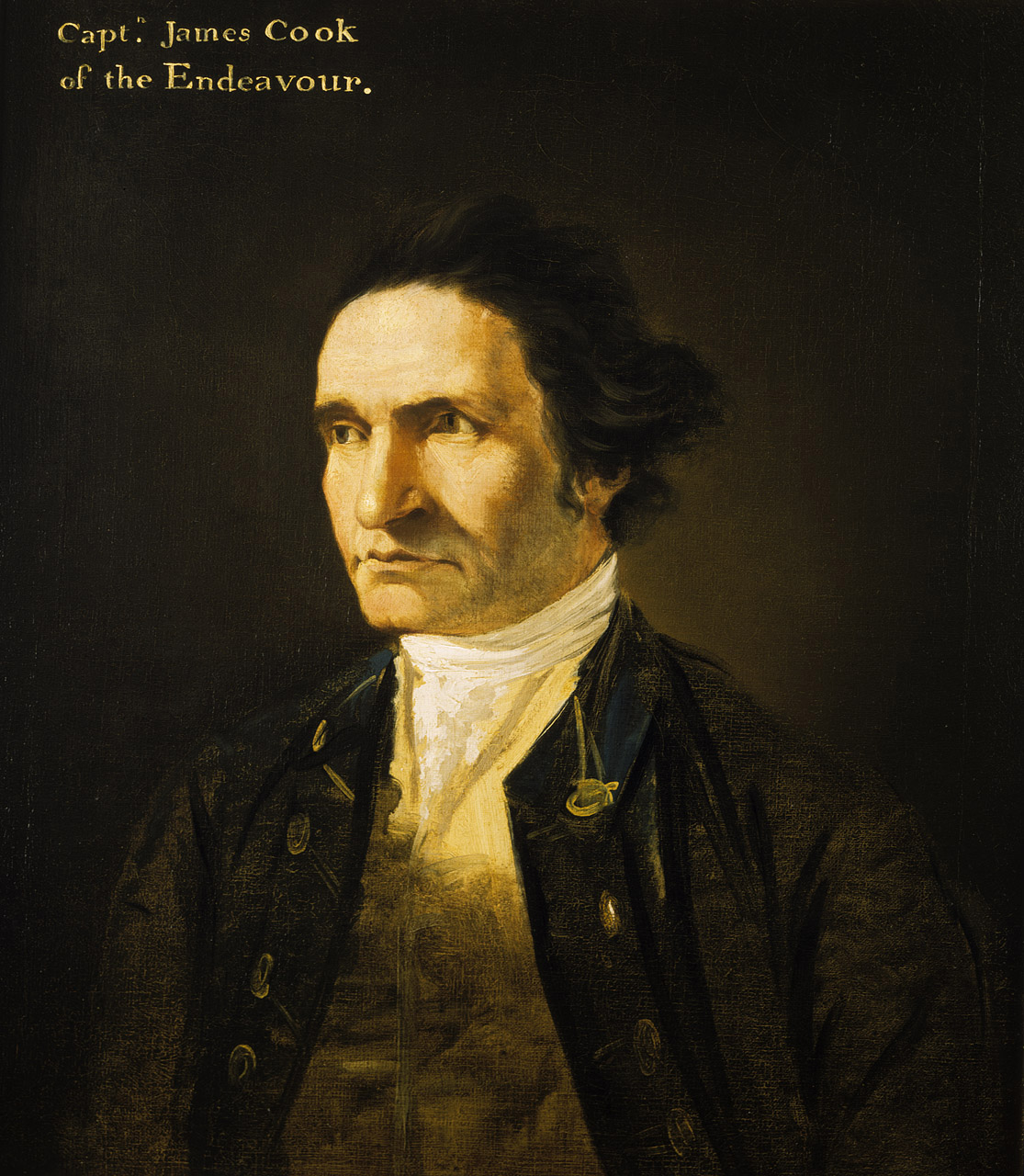

Of the Canberra and the Greenwich Cook portraits, the Greenwich's is easily the most desirable for its realism. He wears his famed weather-worn resolution untainted, unlike Canberra's, by talcum powder.

Cook joined the Royal Navy in 1755, aged 26. During his early career he showed great ability as navigator and surveyor. This made him a good choice to command three voyages to the Pacific Ocean.

William Hodges, the artist appointed to record the second voyage (1772–75), painted this portrait either towards the end of the voyage or shortly after his return to Britain.

The failure to muster support for it in Australia in the 1980s underlined the weaknesses in the chain of command to the HQs of global auction houses and gives the lie to the belief that they are infallible.

No one knew about it here or what it conceivably could be. Yet having the global auction houses here was supposed to give Australia at least a level playing field for securing material of value to Australia while Auctralian attics were emptied of their treasures for the international market.

It is true there was nothing in terms of provenance at the time nor other counter evidence to suggest that Sotheby's had a lost chef d'oeuvre on its walls in Ireland. So no urgent messages were sent out to Australian institutions to muster any bidding.

The story highlights the acumen of the Mayfair London art trade which cashed in on both the Webber and the Hodge portraits in a grand manner.

That the visit of the real Hodges Cook - the sleeper - to Sydney, has escaped attention may lie in its presence alongside an array of replicas in the exhibition. These are brass instrument copies of the machines which were invented to help sailors work out their position in the world's oceans. This is what the current exhibition in Sydney seeks to explain.

The inclusion of the Greenwich Cook in the exhibition when the organisers might have satisfied themselves with a replica shows an exceptional commitment to authenticity that one might expect of an exhibition from the National Maritime Museum, Greenwich two years down the track from the event it commemorates – for announcement of the prize.

It must still have bumped up insurance costs no end.

It pips the other major sleeper of Australian interest which has no "Australian" story content. The second best sleeper was the negotiated purchase in 1994 for $1 million – till then its biggest ever individual outlay - for a painting which went through the saleroom just a year before for $165,000.

The work is by the Flemish artist who became chief painter to Charles I, Sir Anthony van Dyck, Portrait of a Seated Couple. It was acquired from the New York branch of Colnaghi's, the London picture dealer.

The picture was originally consigned by an institution with which Sotheby's chairman, Mr Alfred Taubman, has connections. There were red faces at Sotheby's as Colnaghi's in turn had paid only $US109,750 when the portrait was offered for sale at Sotheby's in New York on January 15 last year.

Crimson faces, perhaps because a Michigan-based property magnate, Mr Taubman was an honorary trustee of the Detroit Institute of Arts. He was also president of Sotheby's which catalogued the portrait very conservatively as "attributed" to Van Dyck.

Mr Ron Radford, then director of the AGSA pointed out that the work had been accepted as a Van Dyck since 1922, although donated to the Institute as the lesser artist Cornelis de Vos.

Colnaghi's Nicholas Hall, dealer to James Fairfax in the Australian media heir's later collecting years, told the writer that looking at the illustration in a catalogue of the sale on a flight to the US the sun lit up a spot which convinced him immediately that the work was by the great 17th century Royal portrait artist.