Born in 1844 Swynnerton enjoyed many brief obituaries and some comment in the Australian press when she died in 1933.

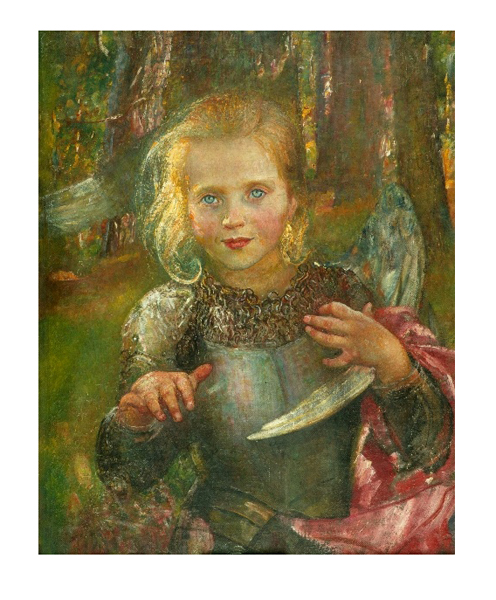

In 1904 the National Gallery of Victoria purchased a work called Hope which fitted beautifully into the title of the current exhibition, Annie Swynnerton: Painting Light and Hope.

Swynnerton’s work could be very sentimental and therefore went quickly out of favour.

Some images of Swynnerton’s Hope, used in several of her works, display her ambitions for the Suffragettes whose causes she anticipated and which is another factor behind her revival. 'Votes for women's centenary' is hot.

Although still unknown, the most notable recent Antipodean dug-up has been the painter of the Sandridge rail terminal, transformed from a sum of $95,160 (including buyer's premium but excluding GST on the buyer's premium) at Sotheby's Australia to an asking price of $148,000 (including GST) in a catalogue published by Sydney’s rare bookshop, Hordern House.

The name Cust appears on the rear of the work, a name more closely associated with a London scholar who had a few memorable words to say about the colonial visitor Marshall Claxton (1811-1881).

The topography – early Sandridge (now named Port Melbourne) railway station and attractive composition – also helped.

Much of the revival in the art of Bock, a colonial artist, and other dug-ups is due to the new ways it is being looked at. This is thanks to a major revision of Australian history in the light of the sorry said to Aboriginal Australians.

As time passes many of the more recent artists who received little uplift in the 1980s proliferation of dug-ups could be candidates for rediscovery. Because they were only just beginning to paint mid to late 20th century they had barely enjoyed their first rush of fame.

The artists which are now being given their due - but were not then - include Stanislaus Rapotec (1913-1997) and Peter Upward (1932 to 1983). Rapotec's chef d'oeuvre was recently sold by Melbourne dealer Charles Nodrum to the Art Gallery of NSW for $200,000 and one of Peter Upward's best works was sold by Sotheby's Australia for an auction record of $329,000.Some potential candidates' works may also have been simply thrown out.

Many abstracts, however, may have been destroyed or otherwise thrown out because of the naturally large discounts attached to abstract art. Buyers may have felt they are being conned because they do not know for sure what the subject is.

It is hard now to appreciate that John Peter Russell (1858-1930) was a dug up in the 1930s thanks in part to the London branch of Wildenstein’s. Many Australian artists who spent much of their time overseas could also qualify.

But the new take on this artist evident in the fine exhibition at the Art Gallery of NSW was his recognition as an international artist in the mould of the “real” Impressionists of Europe.

The exhibition showed the views of Belle Ile which led people to call him the Australian Monet were not as demonstrative of Russell as an international Impressionist as he has been reinterpreted.

These qualities do not now stand out in the Belle Ile stormy pictures as much as in his other works.

Take the later works of Tudor St George Tucker (1862-1908). In the 1970s, arch fossicker Tony Cowden tracked down the owners in the English seaside resort of Weston Super Mare of a pile of paintings that may well have been by the artist.

Cowden was told by the residents, the only members of the artist's surviving family he could track down, that works that fitted the description of the artists were left out for the garbage men only a few weeks before his arrival on the resident's door step.

Another dug-up, Edgar Bult is the subject of an article by Robert Stevens in the latest issue of Australiana, the journal of the Australiana Society. Bult is an artist of the old colonial school that had a good run during the 1980s.

But now, voila! Meet the working-class artist in an age when if anything is on the nose it is inequality.

Edgar or Edmund as he was also known used to enjoy a rather modest reputation as an artist who came from a family of butchers. We are led to believe that Bult as the younger brother in a big family is unlikely have been able to join the family business, so became an artist instead.

Not that the author, Stevens, pursues this, but over 13 pages the case for the artist is dutifully made.

This is notwithstanding his identification as an artist who broke and entered (not an uncommon career path for some of the early arrivals), possibly "drank", apparently had a life of "opportunities offered, accepted but then at least partially wasted".

He was "very conscientious with his engraving, portrait painting and teaching, establishing high standards".

The magazine underlines the difference between the current and past interpretation of Australiana by its inclusion of a critique by John Hawkins, a former president of the Australian Antique & Art Dealers Association of the exhibition Colony: Australia 1770-1861 at the National Gallery of Victoria at Melbourne's Federation Square.

Hawkins was so disappointed that he never visited the second part of the exhibition: Frontier Wars in another section of the gallery. The exhibition was supposed to be the most comprehensive presentation of colonial art to date. "Old style curators with their deep wells of hard-won knowledge pioneered and maintained the current wisdom encompassing this complex subject, using a methodology based on research and visual precedence" Hawkins writes.

With 600 items in the two shows Australiana is making a comeback but clearly in a different guise as the title Frontier Wars suggests. In the past Aborigines had emerged as something of a nuisance.

Hawkins laments the absence of a curator of Australian decorative arts at the National Gallery and the shedding of curators in favour of generalists (staff with no curatorial expertise) at all in other institutions. “This suggests a lack of pride and interest in our achievements during 230 years since British settlement” he says.

The grand and the vainglorious period of early Australiana may be on the nose among the “generalist” curators that are under attack from some of the old school traders and collectors – from the extensive period of great Australiana boom that preceded the Bicentenary of European settlement of 1988.

But at least it has returned the early Australiana market into play. And this is not necessarily due to the regular revolutions in the market place in which modern and contemporary art move in and out of eminence as the best examples of the old disappear from the market and collectors become interested in the latest of the new and vice versa.

The rise of the dug-up with the recognition that there can be new life in an old story suggests that it is well worth holding on to a lot of work that may have gone out of favour. It could well come back again for a different reason.