The skullduggery could even be said to have begun with some of the earliest “art” to be traded on the other side of the ditch, tattooed Maori skulls when fake identities were created in the 1830s for misappropriated skulls.

On October 14 in Wellington art crime resources therefore enjoyed a timely mobilization - for the third successive year. The intensive annual symposium at the City Gallery, Wellington covered a very diverse spread of art crimes perpetuated across the ditch ranging from fake Ming porcelain and missing murals to illegal street art, public perceptions of art crime and the media’s response to the ram raid itself.

The day long program of talks and discussions was held by the New Zealand Art Crime Research Trust with a panel headed by Wellington District Court Judge Arthur Tompkins who has authored a major international book on art crime and its prevention and has written another Plundering Beauty, A History of Art Crime during the War which is to be published next year in London by Lund Humphries.

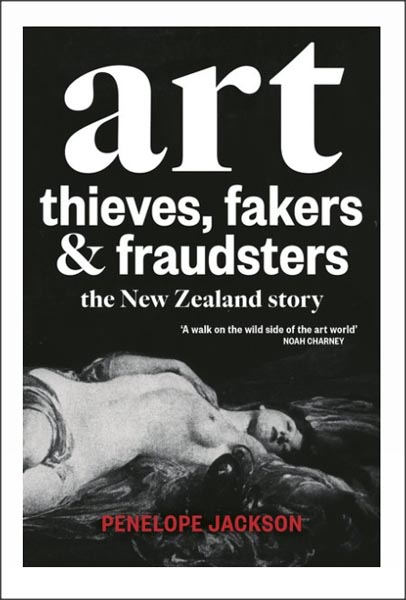

The publication follows the appearance of another book on art crime examining the local art crime context by Penelope Jackson, an art historian who is the former director of Tauranga Art Gallery. Her book Art thieves, Fakers and Fraudsters published by Awa Press, Wellington is as riveting as its title suggests and yet may not still be the full story.

The publication and the symposium were timely for art lovers on both sides of the Tasman given the court case involving “fake” Brett Whiteley paintings in Melbourne.

But the case’s failure to secure a conviction was seen as a set back to the elimination of fakes of other art jiggery-pokery which, however, seems to help sell newspapers and fascinate TV news viewers.

Journalists, who were strongly represented at the well-attended symposium, agreed they had to resolve their inevitable ambivalence on art crime, welcoming the latest scoop while deploring its incidence.

As Noah Charney said in his review of Penelope Jackson’s book, the story can be “a walk on the wildside.”

Art crime has so far been accepted with a smile because it has not involved violence and injury to persons. The Lindauers for which a sum of nearly $New Zealand1 million was expected in a forthcoming auction, have not been recovered but the shards of glass which shattered when the first vehicle failed to break the window and a second was driven in, must have cut into the paintings.

While ever bigger money is involved, art criminals tend to be viewed by the public as romantics who enjoy taunting a business which can be guilty of the snooty put-down. So a reverse put-down is quite in order.

It should not surprise that art crime has a big edge in New Zealand despite the small population. Among the comings and goings of any suspicious nature must readily attract attention. (The ram raid was fully captured on CCTV. ) It would be difficult to attract a buyer for a stolen painting and theft is one of the most obvious ways in which art can become criminal.

Unlike Australia, however, there is proportionately more art with an international flavor in New Zealand that can be moved to offshore markets. New Zealand was settled basically by the Scots who had a good eye for art whereas New Zealand was settled predominantly by the Irish who have a good ear and appreciation of the written word.

The art came into New Zealand as money to be laundered – a crime in itself- in a country with tight exchange controls. Or it was imported legitimately by the Murray-Fullers, big dealers in art in New Zealand in the 1920s-30s.

Anecdotally, many a masterpiece of British art must have been landed up with New Zealand widows and charmed out of them for song.

While this is technically not a criminal offence, expressions such as skullduggery and jiggery-pokery come readily to mind to complete the picture.

The export of Maori art such as tribal carvings is licensed. No major specimen is likely to be freely permitted to leave the country legally. Portraits such as those by Charles Frederick Goldie and Lindauer also have almost iconic status, some of them sought globally like the work of the contemporary artist Colin McCahon, the subject also of further meanderings in the art world.

Deliberate destruction of art has tended not to arise because of the lure of profiteering from its onward sale. Graffiti, however, can be overpainted in which instance an illegal art work is destroyed, this being a moral outrage.

Painted illegally in the first place the graffiti obtains the status of authenticity especially if the artist or the imagery becomes famous.

Most of the reporting I did for the Australian Financial Review on questionable art dealings in New Zealand related to objects highly valued as relics but without proof of their past ownership. Whether it is just outright optimism and wishful thinking or full deception, an object cannot be accepted for what it is claimed to be without some kind of provenance.

The auction of a boomerang, which is said to have belonged to Captain James Cook, prompted a campaign for a while for the boomerang to be welcomed back to Australia.

The provenance, however, lies in the past ownership which in this instance was limited. I shocked some journalists present by quoting the golden rule of the Chicago School of Journalism in claims of exotic backgrounds. That was “if your mother says she loves you, check it out.” Journalists can be too trusting and gullible.

A work described as the original watercolour by John Clevely for the aquatint by Francis Jukes, offered in Wellington in 1983 as the original watercolours for Clevely’s depiction of the death of Captain Cook presented me with a problem of as to its description.

The sub-editors at the Australian Financial Review for which I was the saleroom writer approved: “Ever so Clevely done” in the Financial Review. Examined microsopically in later years this proved a fair call.

Cook is a word that readily springs to mind as the way some of his supposed relics have been created. Gottfried is another, suggesting burnt fingers.

Provenance in such cases is golden. Later microscopic examination of the supposed death scene showed it to be a print. Such examinations can now be common place and very helpful, the symposium was told.

In Sydney in March 2017 another poser was a waistcoat said to have been owned by Cook. It failed to sell at auction, with bids far below its anticipated million dollar price tag, which seems now to be the going price for notable relics.

Cook, of course is recognised as significant for many places including Hawii, Canada and the South Pacific as well as for the UK.

Unusual variants of the wide ranging nature of art crimes included the destruction of UNESCO-listed architectural treasures of Timbuktu discussed by Suzanne Janissen, a barrister specialising in environmental law and paintings bought honestly and with goodwill by a soldier from Dunedin in World War II and sold on to the local art gallery. They had to be returned to the Italian authorities who chanced upon them and their history when a museum in Italy sought to put together an exhibition of the work of the Macchiaioli or Italian post Impressionists.

Returned, that is for good, not a loan, under international law.

At the International Criminal Court in Amsterdam in 2013, Ahmad Al Faqi Al Mahdi was convicted of the war crime of having deliberately directed the attacks that, in June and July 2012, led to the destruction of ten religious and historical monuments in Timbuktu (Mali), a World Heritage site since 1988. He admitted guilt and conceded his complete remorse at the crime.

He was still sentenced to nine years in prison.

In the opening chapter of her book, Gold from Goldies, Penelope Jackson suggests that a faked label on the back of a painting is the first tick adjudicators put against a work being by Goldie who is considered to be New Zealand’s Rembrandt. The note is 'most likely to be a fake.’

Or it might be by Karl Feoder Sim (1923-2013) who changed his name to Carl Feodor Goldie so that he could sign his name legitimately with the same initials as Charles Frederick Goldie (1870-1947) and wrote a bestselling book about his career.

In New Zealand as elsewhere, fakers most likely are frustrated artists who have had difficulty being recognized for their own talent.

The Maori Feather Box has been documented to have been forged on several occasions by James Edward Little (1876 – 1953). He was an antiques dealer and tribal art restorer who lived in Torquay England and specialized in making and selling tribal art and Polynesian art.