Her absence must be a great disappointment to Australian art lovers because Sir Bertam Mackennal was Australia's first and only sculptor elected to the august institution.

Her inclusion could have given Australian art a great international break.

No other Australian artist achieved quite the kind of international exposure Circe created when it was exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1894, nor the overseas reputation partially built upon it, until Sidney Nolan and the Australian Antipodeans in the 1960s.

But the publicity attached to the 1894 exposure was a source of great embarrassment to the Royal Academy.

It was accused of prudishness when the bronze was exhibited with the figures in its erotically charged base draped over. That, of course, brought only greater crowds.

The absence of Circe from Bronze is clearly is not related to prior commitment to the exhibition at the AGNSW.

The Royal Academy explains that Circe is not in Bronze, because the show is limited to 150 works.

Museums from all over the world opened their doors to requests from the Royal Academy to borrow the expensive to transport monumental works for the show.

Among these works, however, is another work of intense Australian interest because of a copy outside the Sydney Hospital.

It is Il Porcellino (Italian Piglet) which is the nickname for the bronze fountain of a board which has been borrowed from the Uffizi Museum in Florence for the show.

The figure was sculpted and cast by the Baroque master Pietro Tacca (1577–1640) shortly before 1634, following a marble Italian copy of a Hellenistic marble original.

Another smaller copy of the sculpture is a tourist attraction and a well-loved local placement

This copy was given to the Sydney Hospital in 1968 by Clarissa Torrigani of Florence, Italy, as a link of friendship between Italy and Australia.

The stature of works in the Royal Academy exhibition is astounding.

Works of the same, if not greater quality and inspiration than Mackennal's were being done by several other civilisations up to 5000 years ago.

What is particularly exciting is that some of these finds are recent, totally unknown previously, helped by the robustness of bronze as a material.

The exhibition is arranged thematically and brings together outstanding works from antiquity to the present.

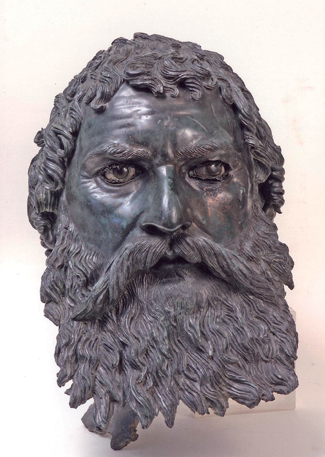

Different sections focus on the Human Figure, Animals, Groups, Objects, Reliefs, Gods, Heads and Busts.

It ranges over Ancient Greek, Roman and Etruscan bronzes, through to rare survivals from the Medieval period.

The Renaissance is represented with the works of artists such as Ghiberti, Donatello, Cellini, and later Giambologna, De Vries (inaccurately speculated as the creator of a sleeper at a Vickers & Hoad sale in Sydney last year, but about which all has since gone quiet) and modern masters, Rodin and Matisse.

Picasso, Moore, Bourgeois and Koons also are representative of the best from the 19th century to today

Recent archaeological finds in the exhibition include the magnificent Dancing Satyr, (4th century BCE, Museo del Satiro, Church of Sant’Egidio, Mazara del Vallo) which was discovered off the coast of Sicily in 1998 and Portrait of King Seuthes III, early Hellenistic period (National Archeological Museum, Sofia), found in 2004 during archaeological excavations in Bulgaria.

The exhibition benefits from an extremely strong representation of Renaissance bronzes which Mackennal arguably in retrospect was merely revisiting.