The Australian art auction industry is having to put in more work for a lot less reward this year.

Figures to date suggest that it will be hard put to match last year's much reduced totals despite taking in a lot more pictures.

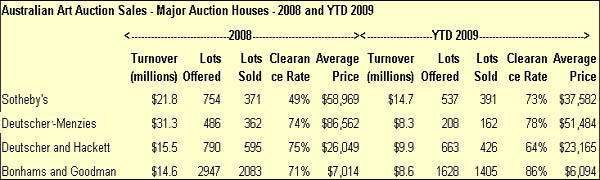

Turnover of the top four auction houses is running at $41 million for the year for the year compared with $83 million for the whole of last year, and the year is more than half way complete in terms of the auction schedule.

It has taken 2384 lots sold so far this year to produce a figure that suggests it will have difficulty matching last year's result, when 3411 lots were sold for the whole of last year.

With the average price per lot down from $28,913 to $17,394 profit margins must be under considerable strain not to mention muscles and mental exercises. There has clearly been a lot more heaving and carrying, letters in the post, accounting, taxi rides and phone calls just in the mere processing of pictures.

That is in addition to the enhanced activity in seeking out lots to sell in a much less predictable market.

Trying to overcome discretionary sellers' anxieties about exposing their holdings to the vagaries of the market, means that vendors have had the upper hand and been able to negotiate very attractive terms.

Melbourne dealer John Playfoot said that his decision to consign 20 plus major to Bonhams and Goodman latest sale in Melbourne was influenced by the very attractive terms he was able to negotiate.

No auctioneer is particularly keen to elaborate, but overseas the auction houses are said to now sometimes pass on some of the buyer's premium to vendors, to secure attractive consignments of work for sale.

Apart from their boost to the auctioneer's ego, the turnovers are important in attracting new business. It is a plus to an auction house simply to have a work, especially if it valuable and boosts the advertisable result.

The auctioneer with the biggest turnover is the head if the pack. In the first months of the credit crisis there was a big push by the major auction houses to become leaner by reducing the number of lots offered and increasing their value. But the industry is driven by stock, and the reluctance of vendors to part with their art meant this was not possible. Vendors held back fearing they would have to sacrifice their works by putting them up for sale

Potential vendors must also have been disillusioned by the performance of financial securities and real estate believing that art remained a better store of wealth that any of the tradition al vehicles.

Even Deutscher-Menzies has not bucked the trend, despite its total, excluding the associated Lawson- Menzies group. The two occupy the same headquarters and their offerings now share the same catalogues. Lawson-Menzies is a less expensive brand.

Sotheby's average lot grossed $37,582 compared with $58,969 previously. Bonhams and Goodman's average is down from $7014 to $6094 reflecting the inclusion of results from its lower end market Bay East rooms.

These figures are based on the number of lots sold. The numbers sold were 391 at Sotheby's compared with 371 for the previous calendar year; 426 at Deutscher and Hackett (595 previously full year) and 1405 (2083) at Bonhams and Goodman.

Even high ground claimant Deutscher-Menzies appears to have taken a hit with the gross lot price averaging $51,484 against $86,852 previously. It has sold 162 works against 362 works previously.

With some heightened reluctance by buyers, ("paddle elbow" as it is now known overseas), affecting some clearance rates the number of lots handled (offered) were Sotheby's 537 against 754; Deutscher Menzies 208 against 486; Deutscher and Hackett 663 against 790 and Bonhams and Goodman 1628 against 2947).

"Other auction" houses have not lost out as a result of the majors to take in lesser lots. They have done $9.59 million for the year to date against $18.59 million for the whole of last year. The figures are not included in the above averages.

Their sales are usually packed and bidding often hectic.

The reduction in high value lots at auction possibly reflects the usual growth in private treaty sales that comes in hard times. People go private because they do not want to be thought to be under financial pressure or because of the unpredictable nature of auction bidding in hard times. A work unsold at auction can be damaged by the public repudiation that this implies. It becomes damaged goods.

An increase in telephone bidding at the more important auctions, suggests a certain indifference to the result and there is much sitting back to see if a lot can be bought afterwards more cheaply. A reluctance to be seen conspicuously consuming is a natural corollary to a world in which jobs are threatened and superannuation has taken a big hit. This, despite the Government's encouragement to private spending to stimulate the economy.

The year has seen some high profile divorces and the other "d's" - death and debt which have affected sales and results.

Both antique and picture collectors are itching to see what comes on the market as a result of the Warren Anderson divorce which has taken some fascinating turns (Antiques at Fifty Paces, Andrew Hornery, Sydney Morning Herald, June 6.)

Debt problems have intensified with the most highly publicised the sale of the financial pressed Austcorp Group Ltd's art on August 25 in Melbourne. This sale also contributed to Sotheby's lower average price per lot for the period as the 173 lots made only $891,520. While flying in the face of Sotheby's previous stated push to lift the value and therefore reduce the number of lots sold, no auction house could have turned this sale down, as it heightened the winner's visibility at the big end of town.

The credit crisis and its ramifications also featured in the sale of the collection of the Naval and Military Club in Melbourne by D and H on August 26.

Sales driven by debt, divorce and death are more likely to be clearance sales but there is a certain saving on effort as one truck, for instance, carries all or most of the work to the auction rather than discretionary sales which involve lots of trips.

Death has fulfilled its traditional role as a major supplier of stock to the market with estates sold this year including that of Rona Eastaugh by Sotheby's in Melbourne on May 4, and that of the late James Gleeson on August 27 Bonhams and Goodman. Other sales have featured works from the studios of the of sculptors the late John Dowie and Barbara Tribe.

Sotheby's lower value per lot may also reflect its lead position in the Aboriginal art market. Vendors of big ticket lots of Aboriginal art tend to have taken advice that now is not an ideal time to sell. The huge volume of work released on behalf of artists over the past four decades has lead so some anxieties about the market being over-saturated.

However, the market continues to sort itself out with enterprising rug and household contents auctioneers taking up some of the slack at the lower end where high profile auction houses might be reluctant to tread. Quality is very much in the eye of the beholder.

* Sold for $420,000 to a syndicate in 1986, David Davies The Season of Storm, Stress and Toil hung over the market until long after the recession broke in 1996. Its title sums up this year in the saleroom