In the light of the difficulty some of the best Aboriginal art has in finding dealers to handle it, Newstead also mounts a passionate defence of a broader interpretation of provenance than that traditionally employed.

He does this in a closely traced and personally followed, almost diary-ised account of the labyrinthine movements of the market from its inception during which he has been both a dealer and auction manager.

This has covered several decades in which Aboriginal art has clearly been his life and joy.

He is critical but without bile conveying some of the great humanism he has encountered on the way and fixing in print with magnificent adjectival prose, the images of artists that would otherwise have been lost for good.

The book is at times a rollicking good yarn about what at times becomes both grand and soap opera (Newstead's own words) with his empathy naturally greatest for those who need to be valued highest in the marketplace – the artists.

It has been hard for an artist to live the life a La Boheme in Australia. Blessings like a benign climate (no one freezes to death), art prizes, tax incentives (gifts in kind and the now foregone under superannuation concessions), scholarships and, in final reserve, there is the dole.

All these considerations have made it hard for the artist to starve in a garret as collectors expect them to. They want to know that artists have suffered for their art.

Aboriginal artists do not find it so difficult to live such lives mostly because of the conflict of values with western society.

The plight of Namatjira, a true “Bohemian” who died penniless charged with buying alcohol for his mates and nearly losing his honorary citizenship, is inevitably highlighted in this encyclopaedic tome.

Newstead sticks by his early observations about the inadequacy of the droit de suite as a way to ease some of these pains.

The long term strategy of effectively penning artists into the art centre making it harder for them to desert to the “carpet baggers” is also challenged.

The Dealer is the Devil leaves off history where the exponential growth in sales which began with Papunya Tula in 1972 came to an end in the mid 2000s.

Australian Art Sales Digest subscribers will be most interested to read what Newstead says about auctioneer and industrial cleaner Rodney Menzies for whom Newstead with the help of Kerry Williams, set new records for dozens of artists when presiding over Lawson-Menzies' auctions of Aboriginal art from 2003 to 2008.

Partly through acceptance of fine works not provenanced to art centres Lawson-Menzies generated sales of $3.7 million of a $15.9 million market, cutting Sotheby's overwhelming dominance of the Aboriginal art auction market reducing it to 54 per cent of total sales.

A log-jam had developed in sales as a result of the “provenance” issue design to protect artist from independent dealers by keeping artists within a supposedly protective fold – despite this being arguably an inappropriate trade practice as it kept prices down.

Either way many an artist was not always appropriately rewarded for their excellence and application.

Unstated as such, misinformed journalists appear to be more of a devil of the title than the so-called carpet- baggers because they distorted prevailing opinions on provenance.

A named journalist from the Australian who portrayed independent dealers as "exploiters of defenceless Aboriginal painters” appears to be Newstead's bete-noir.

The Lawson-Menzies operation hit a cross road as Menzies sought to up the ante on sales while Newstead took a more curatorial gamble on emerging artists.

As a result of its withdrawal, the absence now of any major auction house to champion them such as Lawson-Menzies “countless genuine art works are rejected and the notion of their collectability is compromised,” he says.

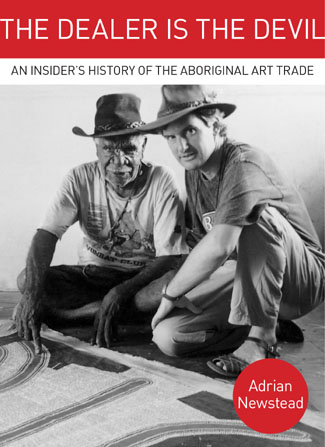

From a London East End family which lived north of Bondi and enjoyed the high life in 1950s Sydney after suffering the deprivations of the war, Newstead had no formal art qualifications but has inherited his family's new found Australian zest for living.

Newstead dismisses anxieties about Aboriginal artists family members completing an artist's work. He ridicules buyers who ask “Could Emily have done every dot herself?”

The highly successful British artist Damien Hirst is one of many overseas having assistants do some of the work and it was common from Renaissance times.

Newstead's 500 page paperback tome is helped by the author's adjectival command which deftly in remarkable economy of works, captures the character or physical profile of a subject.

Take: ”One of the most important curators of the period was Anthony Bourke, who was nicknamed Ace for his form on the tennis court. Tall aquiline, cultivated and fastidious, Ace would have made a name as an international curator had he moved in a different milieu to the Sydney of the times."

He describes the Kempsey NSW artist Robert Campbell Junior as “A big gentle country fella “ and of his work “Themes of racism and the effects of alcohol in rural Australian towns dominated his distinctive, formally arranged, brightly coloured paintings.”

While he concedes that in its later years the industry sometimes turned into a “soap opera”, he appears to have known nearly every one who counts and has an uncanny ability to sum them up in a brief few words.

Newstead's observations gain greater strength from being able to draw on the experience he had in the push for Aboriginal rights in Australia in his youth.

But he offers no insights into where the market may be heading. The book implies there may be a few good paintings out there in the big pile which should not be relegated to the culture bin (St Vincent de Paul's) and to buy on one's gut response.