The books' reveal how the two pilots, Lady Maie Casey and Taft-Hendry, respectively helped tow Australian and New Guinea art into the loop during one of the market and Australian society's most parochial periods.

They also show Australia very much in touch with if not ahead of the rest of the world at a time it was supposed to be very regressive.

When Papua New Guinea was still in parts emerging from the Stone Ages in the 1950s and 1960s Senta was flying Cessnas around the Australian colony. She cast her net widely and like any trawler acquired both the fine and the not so interesting.

The opening of her cargoes at her Paddington, Sydney Galerie Primitif were big events for a small group of dedicated circle of collectors and she saved many of its specimens of an important Oceanic culture from destruction.

Montana's book on Sainthill highlights the much overlooked impressive connection Australia had to the British art world in the immediate pre-and post World War II period.

This was through Loudon Sainthill, the artist who is the subject of the book, his partner Tatlock Miller and the owner of London's Redfern Gallery; and “the homosexual aesthete” Rex Nan Kivell who for a time employed Miller as manager.

Sainthill's leading patron Lady Maie Casey was the wife of Sir Reginald Casey, a military man whose diplomatic posts included Washington.

In the US and back home in Australia Lady Casey she was a fierce champion of Australian art giving helping influence the authorities to buy for the National Library of Australia the New Zealand expatriate Kivell's collection of colonial art garnered from around the globe while he ran the Redfern in London.

In Melbourne her apartment at Alcaston House in Collins Street was a salon for artists including Sainthill to whom she gave several major design commissions.

Montana maintains the very liberated Lady Casey was at the head of a push that made Australia was far more advanced in its social mores and links to international art than has generally been conceived.

Photographs of the “confirmed bachelors” Miller and Sainthill together in their apartment also at the Paris end of Collins Street were widely published in newspaper and magazine articles of the time. Montana point out that no one publicly asked questions about this. Australia was more socially inclusive than has ever been made out before.

Lady Casey encouraged a variant of the elite world of English modernism and its place in British town-houses and country residence.

He suggests it was probably Casey who helped Sainthill get the job of designing the colour scheme of silver, gold wine and blue of one of social identity Sadie Sadler's wedding reception décor in Melbourne in 1938. Loudon also did a mural for Lady Casey's kitchen which he titled Edwardian Hopscotch.

She took Sainthill's paintings to Washington where she would promote contemporary Australian art when Lord Casey her husband became ambassador.

Lady Casey and Taft-Hendry flew planes in very different circumstances. Lady Casey's flights were in mainland Australia and the United States. She flew a circle around the Statue of Liberty.

Taft-Hendry flew over the jungles of Papua New Guinea where Ellis Rowan, another artist whose reputation blossomed as a result of Lady Casey's later interest in her work and career.

Lady Casey called the planes she flew, which were Miles Messengers and Cessnas, her “babies.” But it is a real child, not an aeroplane, which as the subject of a portrait by Tom Roberts, points to the breadth of her patronage.

It is one of the great paintings of Australian Impressionism which will be offered in Melbourne by Sotheby's on May 13.

But in its recent history the picture has lost its Casey provenance and the work still appears to be struggling to find it.

When it was last offered in Sydney through Christie's in 1988 when Sue Hewitt, a former aid to the Caseys, was running the company in Australia, Casey's name was omitted apparently because, as the Australian Financial Review reported at the time, the family preferred it that way.

Sotheby's has now sent Australian Art Sales Digest “some” of the provenance of the picture now to be included in the catalogue.

There are two private collections and a couple of named ones but Lady Casey's does not yet appear.

The AFR reported October 20 1988 under the headline Family Veto on Lady Casey's Unseen Child that “the family of the late Lady Casey, or her beneficiaries, obviously thought that little girls should be heard and not seen."

They were unable to prevent previously published information on a Tom Roberts painting, Portrait of Miss Minna Simpson, being reproduced in Helen Topliss's catalogue raisonne of the artist's work.

But they refused to let the author see the painting, or to allow it to be photographed for reproduction. This was despite her name appearing on many earlier loans of the works.. \

The Australian Art Sales Digest shows the painting offered at a tricky uncertain time for Australian art, became what is now the sixth most expensive painting by its master Impressionist when it made a short of estimate total IBP of $254,545.

Sotheby's now has an estimate of $300,000 to $400,000 which could take it into number one territory in the estimates given the top price is now held by A Mountain Muster sold for $460,000 in 1995.

The book should do much for the slim market in Sainhill's work, much of it connected to the theatre, although it has already made a come back recently when top lots were sold by Deutscher and Hackett.

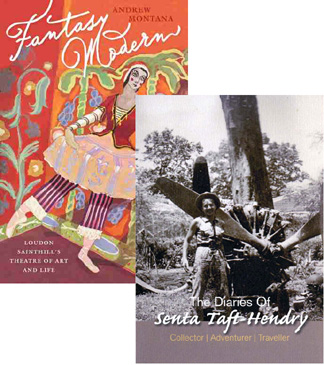

They came from the collection of Lex Aitken and Alfredo (Bouret) and were sold last year for up to $9000, not setting a record for the artist but solid for gouaches of their type. The second pilot, Senta Taft-Hendry is pictured on the cover of the book with a title which includes her name in front of the Cessna in which she flew around Papua New Guinea in search of Sepik and other art.

The Diaries of Senta Taft- Hendry, is a slim home-spun volume into which a few gremlins have appeared.

The now octogenarian might have spun into four volumes if there is anything in the stories that are

told in the tribal art market about the proprietor of Sydney's long standing Galeries Primitifs could be substantiated.

But it helps flag the role the German-born 1939 immigrant whose jet setting life began as a publicist for the carrier Trans Australia Airlines, played in fanning interest in tribal art and gaining its release with help of district officers in the former Australian colony most of whom she knew.

Older buyers of the Senta Taft-Hendry diaries may feel sort changed by the publication given the enormous reputation she has gathered as a collector, adventurer and traveller although it also comes with a CD with a journalistic interview which also conveys even more insight into the extraordinary personality of the great pursuer and trader.

But she was not one to big-note herself and at $40 it offers an introduction to a very lively world little known to most Australian art collectors.

She was famous among the many District Officers Australia sent to the colony, some of whom chased her around the rooms as she tells it.

But the petite and very attractive trader was very focussed. One current trader collector recalls the first thing she said to him when introduced was “how much do you weigh?”

He then realised that she was so slight that she needed “ballast” as much as company for her plane trips.

She thanks her former gallery manager, Leo Fleischmann who she took on one of her trips to New Guinea for a week, and who built on that to develop a remarkable feeling for tribal art. His collection was sold in 1992.

But there does not appear to be a photograph of him in the book or recollection of his dealings.

So hopefully there is more to come. The photographs do not show any obvious masterpieces either.

In this lower echelon market she built up a strong following which came in strong numbers to support the author for the book launch at her gallery on March 17.