Many an industry has a bearing on Australian art, for example the motor vehicle industry of the 1970s when galleries and auctions were in play amongst vehicle dealers: think Doug Fugger, Ron Hodgson, Julian Sterling and Emmanuel Margolin. But the influence of “dips” – real and imaginary - is only now coming to light. For the third time in Australia the creation of an extraordinarily profitable concoction has helped bring to the fore outstanding artistry and talent.

Kiwi boot polish appears to have followed Helena Rubinstein’s Crème Valeze and Douglas Cooper’s sheep dip as underwriting some of the art world’s most adventurous changes in art ownership.

Helena Rubinstein’s dip was full of secret ingredients, a beauty product in which lanolin was believed to have been a key infusion. The fortunes from her “dip” helped Rubinstein not only to support a prestige art prize, but later in the US helped create the market in tribal art as well as early modern western painting.

Cooper’s sheep dip required complete immersion of the animal. Put in the same cupboard by accident, confusion between the two could create a disaster. Helena Rubenstein said there were no ugly women only lazy ones. She was not one of them but one of the greatest female entrepreneurs of the 20th century.

However, Cooper ‘s dip had no direct bearings on the fortunes of Douglas Cooper as was widely reported throughout the 20th century. The Franco-Australian, Douglas Cooper, who was a leading art critic and migrated to Provence was a big fan of George Braque and other cubists. The story at that time was that every time a sheep went into the dip the animal went “Bra-a-a-aque”, earning Cooper money to buy another George Braque.

Cooper inherited a fortune from Australia including property. But the dip was created by a member of the Dorset branch of the Cooper family who migrated to Australia.

The Braque dip story is attributed to a rival art critic who had his Coopers confused, either deliberately or accidentally, so the substance is a dip only in the sense that dips are concoctions.

The father of Hugh Ramsay the artist, emigrated to Australia from Scotland in 1878. The Kiwi boot polish business founded in 1906 was named in honour of a New Zealander who joined the family by marriage.

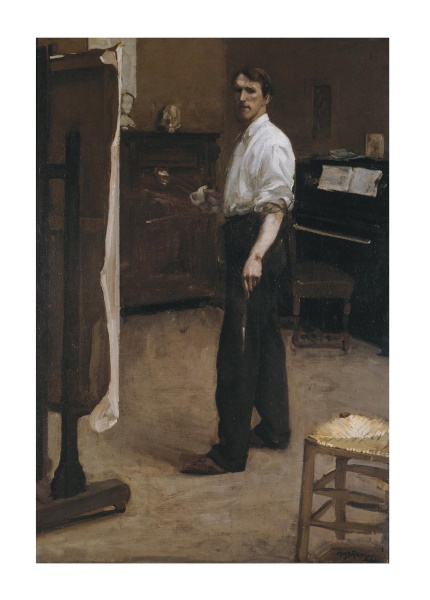

As a young man, Hugh Ramsay found his way back to Paris. Four of five paintings or his paintings were submitted to the New Salon in Paris and were accepted and grouped together, an honour normally extended only to members of the Société Nationale des Beaux Arts.

The paintings were Jeanne, A Lady of Cleveland, U.S.A., René Puaux and Still Life: Books, Mask and Lamp.

Impressed and grateful for his help, the artist Ambrose Patterson introduced Ramsay to (Dame) Nellie Melba who invited him to paint her full-length portrait in London. It was never completed but one portrait of her is in the National Gallery exhibition which opened this month.

In Paris, Ramsay stayed with Longstaff who, like Melba, introduced his connections. John Singer Sargent's works at the Royal Academy impressed him profoundly. Ramsay seemed on the brink of success but within weeks of his arrival his doctor diagnosed tuberculosis, caused by the overwork and poor living conditions during two winters in Paris.

Hugh Ramsay's short life did not of itself reduce his available oeuvre but the family’s support by way of helping discretely point his works at particular institutions did.

That and the commissioned nature of the portrait market has further diminished availability of Ramsay's works, although it assisted to have the global painter Longstaff and Nellie Melba as a patrons. He painted an early portrait of her but not the grand one that was being planned in the last stages of his life when he seemed to be successfully borrowing time.

Many of these works are in the exhibition, thanks to the family whose members now include James and Diana Ramsay whose benefactions to the Art Gallery of South Australia included contributing funds for the $4.6 million purchase in 2014 of Camille Pissarro’s Prairie a Eragny, the most expensive acquisition in the Art Gallery of South Australia's 133-year history, first reported on this website.

The free exhibition Hugh Ramsay was launched with an opening seminar at the beginning of December, the popularity of which almost embarrassed the NGA due to the shortage of stools, requiring participants to carry their stools around the exhibition.

Expecting a large turnout for its blockbuster exhibition titled Picasso / Mattisse a week later, staff at the National Gallery of Australia appeared surprised by the attendance of a crowd of more than 150 for a group of talks on an artist with the far less global name of Hugh Ramsay on the second day of the exhibition on December 1.

The required one metre distance from the exhibits to the visitor's stools was difficult to police and alarms beeped throughout as people passed through the various adjoining galleries housing the seminars as the speakers changed.

The curators were headed by the doyen of modern curatorship Daniel Thomas, who had long retired to Tasmania but who had established the present high bar for scholarship and stewardship of artistic careers at the Art Gallery of NSW in the 1970s.

The interest has been surprising because the artist’ work was mostly portraiture when landscape is generally agreed to be the pre-eminent genre by far in Australia. Despite the artist’s sustained productivity, his short life and limited oeuvre.

The Australian Art Sales Digest records the appearance on the market of only 82 works by him, led by an oil on canvas titled Portrait of a Girl in White, measuring 71 x 54 cm. Estimated at $50,000-80,000, the work was sold for $88,625 by Sotheby's Australia on 29 September, 2015. Many of the works that appear on the market are unsigned nude studies for major works.