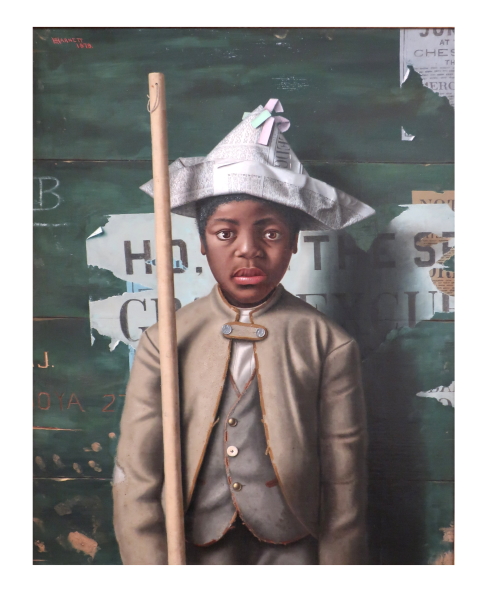

The 91 x 71 cm portrait, Attention Company | Front Face, painted in 1878, was purchased by two Australian antique dealers at a Hobart auction in the late 1960s for $310. It was sold in New York in 1970 for $US67,500.

After its appearance in Hobart, the portrait was taken to the National Gallery of Victoria, which decided it was of no interest.

In the catalogue of the Corcoran-Brooklyn exhibition, the portrait is described as one of only a handful of Harnett's paintings that include people. (Harnett was mainly a painter of trompe l'oeil still lifes).

"Painted in Philadelphia two years before he departed for Europe, it reflects the influence of John George Brown's paintings of children, as well as the polished realism of the French artist Jean-Louis-Ernest Meissonier,"the catalogue says.

"Ironically contrasting the youth's mock battle dress with fragments of peeling wall advertisements that suggestively proclaim 'grand excursion', Harnett's portrait is a moral study in the difference between the fantasy of child's play and the mundane realities of the real world."

The boy is playing toy soldiers, with a broom stick serving as the gun.

Facing History: the Black Image in American Art, is not a warts-and-all view of black people in American art.

Such a view would probably be too cruel, although the more racist depictions are dealt with in the text of the very comprehensive catalogue.

During the Civil War American blacks were often depicted with dramatic heroism, and there was a big market for such subjects among the intellectual abolitionists of the north.

By this time, the romance with which the Australian black was regarded was beginning to evaporate.

In the context of the current exhibition, which closes this month, American institutional interest in Glover's The Bath of Diana, knocked down at a Sotheby's auction in Melbourne to an American dealer claiming to have a US institution in tow, is almost conceivable although that picture, of Aborigines around a waterhole, has still not been paid for, and has been declared a prohibited export.

Compared with the jolly minstrels shown in early American art, Australian artists like Dattillo Rubbo (who painted an American tramp in Sydney in the early 1900s) and Noel Counihan, with his American soldiers at the Cross, have reinforced other conventional views of the American black.

Footnote, Terry ingram writes:

This story was one of several written over the years on the painting after I broke the story in 1979 of one of the most important sleepers ever to turn up in the Australian salerooms, The discovery was proved up as a missing masterpiece by a major Western (US) artist. The portrait might have remained lost for ever had not two Australian antique dealers, Bert Johns and Charles Bremmer, persisted with their belief that the modestly priced work was something special. It was dismissed by a leading curator at the NGV - which was one of their first calls - as of little interest .Surprisingly the art curator who made that call was one of the best in her fields. But her field was renaissance painting. The story should be a reminder the wealth of knowledge or gut feeling is not always institutional. Some of it is has been acquired by members of the trade.